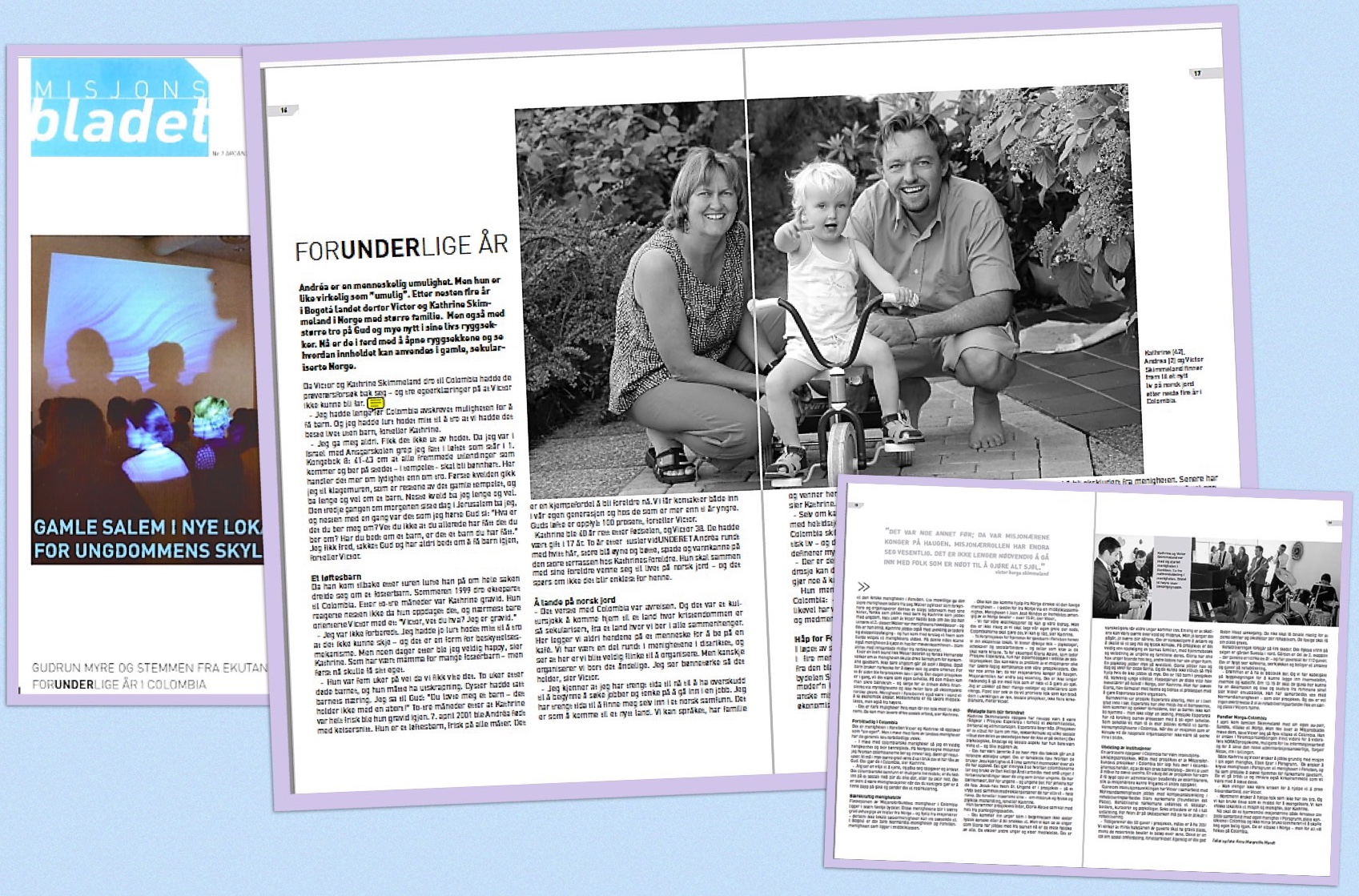

Andrea is a medical impossibility. Yet she’s as real as she is “impossible.” After nearly four years in Bogotá, Victor and Kathrine Skimmeland therefore returned to Norway with a larger family. But they also returned with a stronger faith in God and many new experiences in their life’s backpack. Now they’re in the process of unpacking those backpacks and seeing how the contents can be applied in old, secularized Norway.

COLOMBIA | Anne Margrethe Mandt-Anfindsen | April 7, 2018

English translation by Guy Fava/Claude.AI

LES PÅ NORSK | READ IN ENGLISH | LEER EN ESPAÑOL | LER EM PORTUGUÊS | LEGGI IN ITALIANO

On this occasion of Andrea’s birthday today, Anne Margrethe has kindly allowed me to reuse the article she wrote in summer 2003. Here you can read both about how Andrea came to be through prayer, as we more Free Church-oriented people say, and a bit about what Kathrine and I worked with in Colombia.

(I continued working for «the mission» for a while after I «returned home» to Norway, but only two years later I had earned a new BA of Development Aid and was working full time The Church of Norway and later, in the Norwegian Church Aid (NCA).)

When Victor and Kathrine Skimmeland travelled to Colombia, they had several IVF attempts behind them – and three medical certificates stating that Victor would never become a father.

— I had long before Colombia written off the possibility of having children. And I had tricked my mind into believing we had the best life without children, says Kathrine.

— I never gave up. Couldn’t get it out of my head. When I was in Israel with the seminary, I grabbed hold of the promise given in 1 Kings 8:41-43 about how all foreigners who come and pray at this place – the temple – shall be heard. This is more about obedience than faith, adds Victor.

— On the first evening in Jerusalem I went to the Wailing Wall, which is the remains of the old temple, and prayed long and well for a child. The next day I also prayed long and well. The third time, on the morning of the last day in Jerusalem, I prayed, and almost immediately it was as if I heard God saying,

”What are you asking me for? Don’t you know you’ve already received what you’re praying for? If you’ve asked for a child, it’s a child you’ve received.”

— I found peace, thanked God, and have never prayed for a child again, Victor recounts.

A Child, as Promised

When he returned from the trip, he wondered if the whole thing was about adopting a foster child. In summer 1999, the couple went to Colombia. After two or three months, Kathrine was pregnant. She barely reacted when she discovered it, and almost just casually informed Victor with a: “Victor, you know what? I’m pregnant.”

— I wasn’t prepared. I had tricked my mind into believing it couldn’t happen – it’s a kind of defense mechanism. But a few days later I was really, really happy, says Kathrine, who had been a mom to many foster children but was now going to have her own.

— She was five weeks along when we found out. Two weeks later the baby died, and she needed a D&C. Cysts had taken the baby’s nourishment, Victor explains.

— I said to God: You promised me a child – a miscarriage doesn’t count!

Two or three months after Kathrine had fully recovered, she was again pregnant. On April 7, 2001, Andrea was born by C-section. She’s a promise child, healthy in every way. It’s a huge advantage becoming parents now. We get connections both with our own generation and with those who are more than ten years younger.

— God’s promise is fulfilled 100 percent, Victor shares.

Kathrine turned 40 right after the birth, and Victor 38. They had been married for 17 years. Two years later, the little miracle Andrea toddles around with white hair, big blue eyes, and bucket, spade, and watering can on the large terrace at Kathrine’s parents’ house. Together with her parents, she’ll have to get used to life on Norwegian soil – and it seems it might be easiest for her.

(Story continues below the picture.)

Read article as PDF (Norwegian)

Landing on Norwegian Soil

— The worst thing about Colombia was leaving. And it was a culture shock coming home to a country where Christianity is so secularized, from a country where we pray in all contexts. Here we never lay hands on someone to pray in a café. We’ve been around to various congregations in the district and see that we’ve become very good at organizing here. But maybe we’re organizing away the spiritual aspect. I see a prayer drought that’s overwhelming, says Victor.

— I feel I’ve needed the time until now to have the energy to start looking for jobs and think about entering employment. I’ve needed time to find myself in Norwegian society. It’s like coming to a new country. We know the language, have family and friends here, but things change in four years in Norway too, says Kathrine.

— Although maybe we’ve changed the most. Maybe it has to do with full-time ministry, maybe with the way of living. In Colombia, they don’t separate at all between spiritual and practical life – and they can probably spiritualize things a bit too much. But language defines many of the thoughts that exist, Victor believes.

— There, it’s natural to include God in daily speech. If you’ve taken a taxi, you can say ‘God bless you’ to the driver. I think it does something to be able to ask for God’s blessing, says Kathrine.

She also believes that the experience of time is different in Colombia.

— In Colombia, people have much longer work weeks, yet we have more time there. It has something to do with the closeness to God and fellow human beings.

(Story continues below the picture.)

Time to join my blog. Don’t just be a follower — become a STALKER!

Follow me here .

Hope for Fontibón

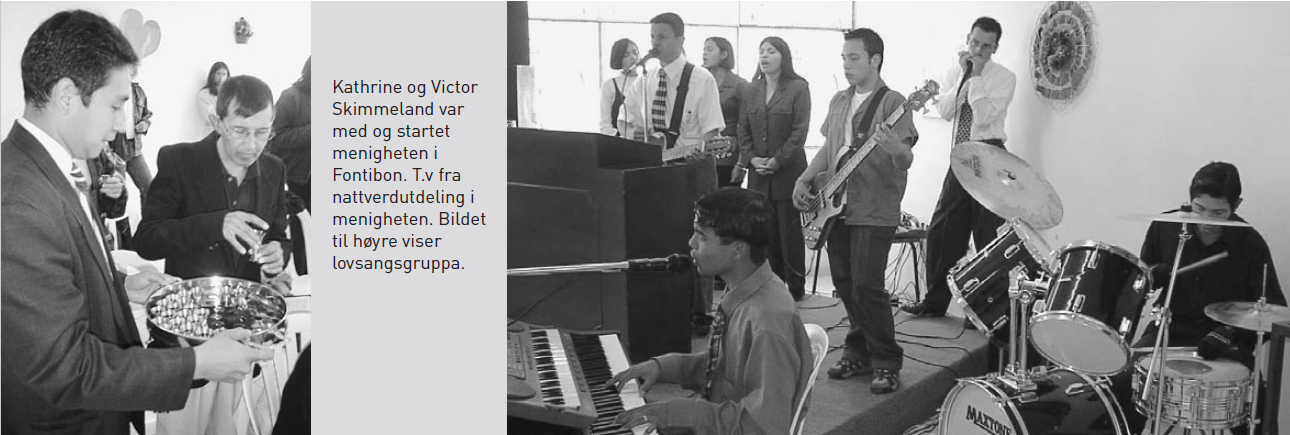

During their time in Colombia, Victor and Kathrine have been part of four congregations. They began in the Soacha congregation in the south. From there, the La-Ye congregation in the north and a congregation in the Sibaté district were founded. The Sibaté congregation came into conflict with the mother church in Soacha and withdrew from FIPEC (the Colombian Mission Covenant Church). In Soacha, financial fraud was also discovered. Victor and Kathrine tried to speak up but ended up being excluded from the congregation. Later, the congregation changed leadership and pastor and is now on the rise.

During this time, their friend Walter Beltrán introduced them to the Fontibón district, which was actually the large district where Kathrine and Victor lived!

Beltrán and Victor Skimmeland contacted the statistics office and learned that the district had 278,000 inhabitants, of whom less than one percent were evangelical Christians. There were many other types of religious denominations, including Mormons and Jehovah’s Witnesses. The two went into intense prayer for the district over a three-month period. They quickly felt a need to ensure that something healthy and solid would grow, so they contacted the Colombian Mission Covenant (FIPEC) for approval and received a preliminary blessing.

— We didn’t want to fish from other congregations, so we invited some of Walter’s friends from the drug environment to meetings in Walter’s home. Then we got a visit from my in-laws who probably prophesied when they talked about circus tents in the garden. We got that. The congregation grew gradually. We wanted people to be saved and added to the congregation. The problem was that we had lots of newly saved people, but only one pastor and one missionary, Victor explains.

The two men went to Bogotá’s largest mission congregation, the Normandía congregation, and asked for some leaders for the fresh congregation in Fontibón. Somewhat reluctantly, the large congregation gave up some leaders. Walter and Victor as preachers and organizers formed a kind of leadership team with their wives, Yanixa who worked with children and Kathrine who worked with youth. Without Victor having asked for it, he was appointed as second pastor. Walter was the congregation’s main pastor – and still is. Kathrine also worked with leadership development and discipleship follow-up – and she made suggestions about who should be chosen as the congregation’s elders. During this time, the congregation also managed to buy a house for meetings – partly with collected funds from Norwegian friends.

After a little while, Walter Beltrán and Yanixa Hernández had thoughts about the congregation running a children’s home for drug-addicted street children. It’s not just youth who use drugs in Bogotá. Children also use narcotics to numb hunger and pain.

A year ago, the pilot project was launched. When the project is up and running, it will be as an independent foundation. This way, sustainability can be ensured – and operations can be partially financed through the authorities and not rest solely on Norwegian donors, for example. The congregation in Fontibón will also be able to take financial responsibility. The members are from lower middle class, but also from higher.

— There are more possibilities if you get people with some financial means. Then you can more easily run social work, says Kathrine.

(Story continues below the picture.)

Exemplary in Colombia

It’s the congregation in Fontibón that Victor and Kathrine now experience as “their own.” But in meeting several of the country’s congregations, they see generally exemplary traits:

— In meeting Colombian congregations, I saw a great devotion and joy in prayer. On Norway’s behalf, I envy how Colombians pray and dedicate themselves. Prayer gives results. We must dare to use what we’ve received from God to a much greater extent. They do that in Colombia, says Kathrine.

— I see a willingness to serve, to take on tasks and responsibility. Colombian society is possibly not very mobile; if you’re born into a social level, you often stay there, or you slide down. It’s significant to be a church servant when what you usually do is find cardboard on the street and send it for recycling.”

Sustainable Church Life

Most of the Mission Covenant’s congregations in Colombia are in very poor districts. These congregations become more dependent on funds from Norway – and help from missionaries – if local sister congregations can’t step in to support.

In Bogotá, only the Normandía congregation and Fontibón congregation are in middle-class areas.

— Often, help can come from Norway directly to the poor congregation – instead of from Norway via a middle-class congregation. The congregation in Juan José Rondón is still dependent on Norway paying – after 15 years, says Victor.

— We have our qualifications and can make our contributions. But it’s not right that we should create our own thing down there. Colombians should do it. We can give advice, says Kathrine.

— For the pilot project for the street children’s home in Fontibón, we brought in expertise locally. We find skilled people – psychologists, lawyers, and social workers – and require that they be Christians. Take Gloria Alzate, for example, who leads Project Esperanza, she has a diploma in leading social projects.

— It can be a problem that we missionaries often have lower professional competence than our project leaders. It was different before; then missionaries were kings of the hill. The missionary role has changed significantly. It’s no longer necessary to bring in people who have to do everything themselves. I’m unsure how many theologians and Bible teachers are needed. FIPEC itself says they want to prioritize people who can assist them in developing new social projects, not more church planters, Victor believes.

Broken Children Transformed

Kathrine Skimmeland’s task has been precisely to be an advisor in Project Esperanza regarding financial management, personnel, and administration. Esperanza means hope. (The project offers children food, adult contact, and various social services during the part of the school day when they’re not in school.) She has only witnessed – and been inspired by – the psychological, spiritual, and social aspects.

— It’s been educational to see how much it’s actually possible to change damaged children. It’s fantastically wonderful how they use Jesus’s love to piece people back together after everything they’ve experienced. It’s impressive to see how Colombians let themselves be used by the Holy Spirit in working with small children. In prayer ministries, they resolve things that bind the children. They have prayer meetings, pray for the children – and the children pray. For the girls, they have an annual Jesus Night. The children are in the project – in a safe place with adult figures they trust – all night. They tell their stories – about abuse and physical and psychological mistreatment, Kathrine explains.

She commends the project’s leader, Gloria Alzate, who has been involved from the planning stage.

— Children come in who initially can’t handle physical contact or being spoken to. But we can see that children Gloria has worked with from the start are now the most physical of all. They comfort other children and show empathy. It’s harder when older children come in: One thing is that the damage can be greater after violence and abuse. But the longer it goes on, the bigger the wounds become. It’s harder to unlearn and to accept praise and physical contact. At the project, there’s very close follow-up with the children’s families, with home visits and guidance for the children and their families. Gloria has often had children living with her, other leaders have taken children home.

A psychologist works a lot in the evenings. Gloria works day and night and lives for these children. And they couldn’t offer so much help if they didn’t work so much. There are 150 children in the project now. Incredibly heavy cases. Most of these would have had full-time support teachers in Norway, says Kathrine. She has supported Gloria, had conversations with her, and contributed to the process of making Esperanza better organized.

The Children’s Protective Services (Bienestar Familiar) take Project Esperanza seriously but is rarely present in the south. Esperanza has often reported to child services, who come and check the conditions, say the child can’t live at home – but don’t offer a solution.

Project Esperanza has now cautiously started the process of becoming an independent foundation. As a foundation, they will have a more positive relationship with child welfare authorities in Colombia. When the mission is the contact, national organizations won’t be as strongly involved.

Development of Institutions

One of Victor’s tasks in Colombia has been the institutional development project. The project’s goal is for the Mission Covenant’s projects in Colombia to be completely transferred into Colombian hands, and for them to operate sustainably – that is, without having to have support from outside. An important part of the project has been building up an administration consisting of Colombians, so that missionaries could be freed up for other tasks. Through institutional development, Victor has worked with Normandía congregation on competence development in rehabilitation work among drug addicts (Fundación El Pacto).

Rehabilitated addicts are educated to become social workers, counsellors, and psychologists. Six workers are now in full education. For each year in school, they must have a mandatory year in rehabilitation work.

— Previously there were 50 boys in the project, the goal is to have 205! We think that at least half of the boys should have free places, while the remaining pay an amount according to ability. This is an idea of social redistribution, explains Victor. It’s really good Robin Hood thinking: The rich should pay generously for their sons and spouses to be rehabilitated. The poor should get their place free.

The rehabilitation takes place in four locations. The newest step on the ladder is the Suesca farm in the north. The farm is part of the second stage – where the boys stay for about a year – and has potential for 110 boys. They’ve built a large cafeteria, industrial kitchen, and housing for staff and boys in rehabilitation.

— The dream is to have a library there. And we have cable channels on the building plans to be able to install internal phones, internet, and cable TV. In 10-15 years, these guys should be able to have a computer and sit and study from their rooms! Victor says enthusiastically. He has worked closely with the Normandía congregation – which owns the project. And it’s probably no exaggeration to say that the rehabilitation work found a special place in Victor’s heart.

Commuting Norway-Colombia

In April, the Skimmeland family returned to Norway with their own au pair, Sandra. But right after Misjonsbladet met them, Victor got on a plane back to Colombia. He’s employed in the Foreign Mission Department for now to continue the NORAD projects, possibly for some information work and to induct the next administration manager, Torgeir Neset, into the position.

Both Kathrine and Victor want to work thoroughly with mission in their own congregation, Eben Ezer in Porsgrunn. They wish to connect the congregation in Porsgrunn to the congregation in Fontibón and have as a project to support the home for drug-addicted street children. They want to reach out broadly and invite even those outside the church who want to help support this.

— You don’t need to be Christian to help run aid work, says Victor.

— Norwegians want to help people who aren’t doing well. And we can use this as a means to evangelize. We can draw local people to mission and congregation, says Kathrine.

Now these two returned missionaries will both continue their good cooperation with their own congregation in Porsgrunn, maintain contacts in Colombia, and not least use the summer to acquire their own housing again. They’re back in Norway – but forever hooked on Colombia.

Victor Skimmeland haa studied theology and works in church and missions. His blog is currently located on preacher.no Copyright © 2018 Victor Skimmeland. All rights reserved. Ask me before any reproduction.